Roff Smith

Journeys from my doorstep

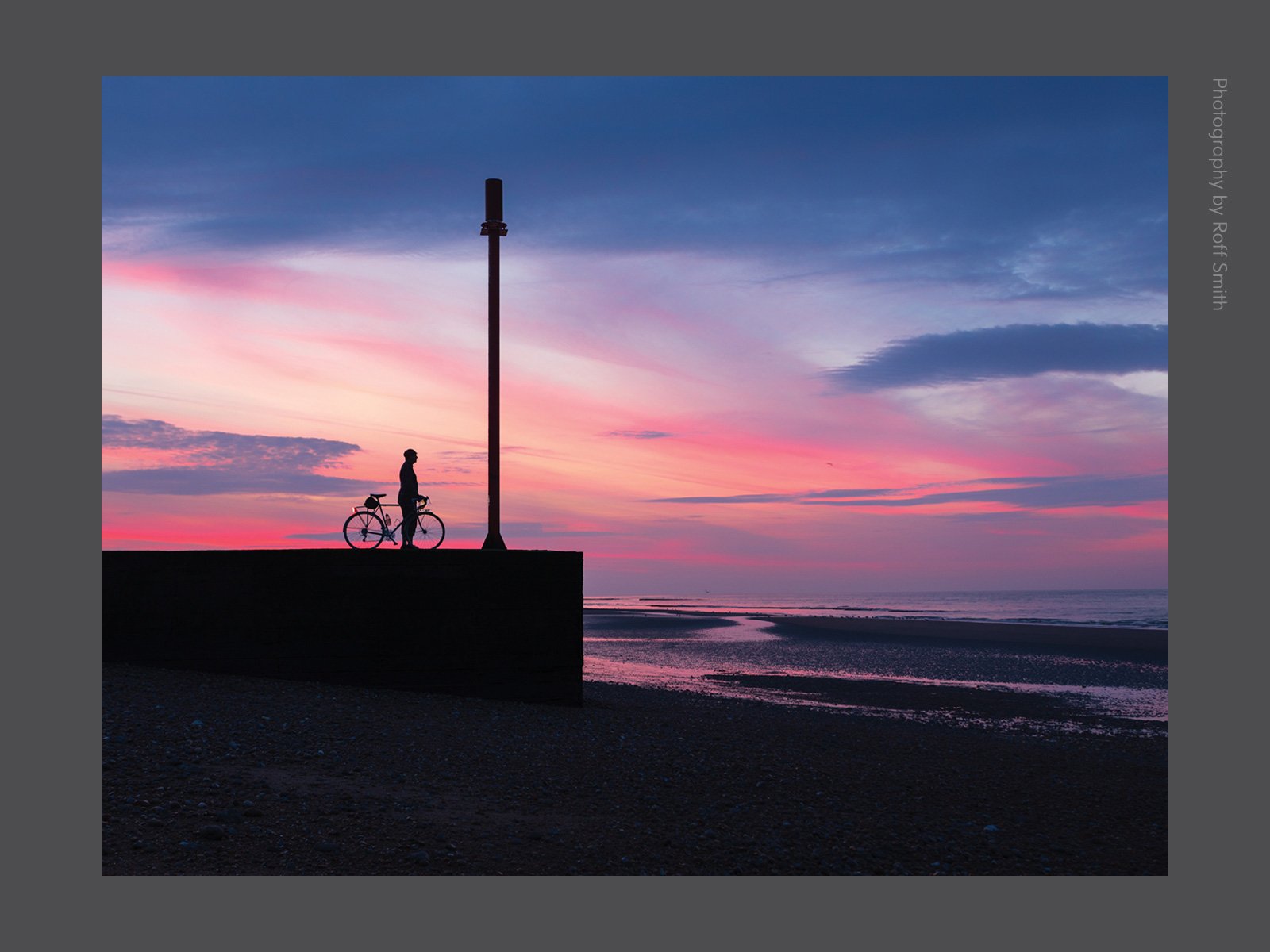

We got up early to witness Roff Smith cycle into the shot as his camera captured the moment that sun rose along Sluice Lane.

You are a writer, cyclist and photographer, please tell us about your background and how it all works in tandem?

Roff. I am from all over; I’ve spent a lot of time on the road. I grew up in New England in the US But I’ve lived most of my life in Australia, and I’m an Australian citizen. And now I’ve lived here in East Sussex for a while.

I’ve always been interested in storytelling. Even when I was in high school, I was writing short stories and interested in art. I would have preferred to go into photography at university, but I studied a degree in geology in the US I did geology because I was into rock climbing, which got me out on the cliffs; I am not a scholar. Then I emigrated to Australia, where I studied archaeology as an MA at the University of Sydney. So one day, I visited the offices of The Sydney Morning Herald to try to get a job as a photographer, and they had something going. Still, it would be mostly sitting around in a dark room, developing images or option two. Mines were opening up all over the country; they needed a mining writer. Now that job was flipping around the country, half of the time flying on corporate jets. Darkroom in the city, or will I swan all over the South Pacific? Well, that was a no brainer. So that is how I got into writing as a finance journalist for a couple of years.

So cycling, I loved cycling when I was a kid, and my dream was to go cycling all over the world. A bicycle is a means of escape, freedom, exploration, liberation. Years went by, I was in my early thirties, and my bicycle was just sitting in the shed gathering dust. I was commuting to a job, as a feature writer, in Melbourne at The Age Newspaper about six miles away. Then the tram drivers went on a long strike; six miles walking in was too far, everyone was grabbing rides from everybody else. I remembered my bicycle, and I thought, oh, I could try riding in. So I did, and after that first ride into the office, I was half terrified and half excited; it was an adventure and a bit dangerous, plus, I still had a ride home at the end of the day! So when the tram drivers went back, I thought I would keep doing this. And it grew from there. So I found myself exploring the city, I was leaving my home earlier for work, so I could have the time to meander, exploring and going through new neighbourhoods.

“My first impression of St Leonards back in ’97 was it seemed quite exotic. Those little lanes and little castle, I had never seen anything like it.”

Ideas began forming, one of them being an old dream to go to Antarctica. I’d always assumed they were things that would never happen or they happened for other people. A new editor, who I didn’t care for, heard my plan about going to Antarctica, and his words were, we’ll see. And I thought, yeah, we will. So I applied for an arts grant, artist in residence, incredibly enough, I got it. So I followed that editor into his office and told him he was sacked. He was no longer my editor, meaning I was off, and he took it well. So I walked around the corner to Time Magazine’s office, walked in, said, I’m going down

to Antarctica. Would you like some stories from there? They said, yeah.

I came back; they liked what I wrote. I also photographed the story. I was there at the time of the very last dog sledge run in Antarctica. It was the last team that was at Mawson’s Base. It was pretty moving. I filed the story for Time, plus a few other stories. And they offered me a staff job; this was a big step up from what I was doing before. I was living in the wine country in Australia and working from my home office. It was like all the joy of a freelance with the security of a staff job. And this was the day when magazines had money; they flew me over for the office Christmas party, with a place to stay. I did that job for a couple of years; then, I decided to quit with many misgivings. I put some stuff on my bike and set off around Australia. I would completely cover the whole continent across about 10,000 miles, solo. Time Magazine, at that point, had a lot of connections with National Geographic; I would occasionally talk with the editors there. So I told them my plan, they were kind of interested. But at that time, I didn’t want to commit. They told me later they were rather shocked cause they offered me money. I wanted to have my adventure. By the time I was about two-thirds of the way around, I had decided I would need money when I had finished. So I said, yeah, I will take that money now, please. So that became a three-part series about my trip around Australia, which later came out in book form, published by National Geographic.

That led to regular work that has gone on now for 25 years. During this time, I’ve covered a lot of archaeology, wildlife, and science; I’ve been back

to Antarctica multiple times, actually 17 times. I haven’t been there a long time now, about 10 years at least, but I covered all kinds of stories for them

all over the world, which is good fun.

What brought you to the South East of England?

Roff. I was cycling around Australia when I met this very nice English girl, my (future) wife. This is how we end up in St Leonards-on-Sea. The very first time I was here was back in 1997. She had taken a year off of her work to travel around the world, she wanted to get away, and we just met by chance in Perth. We were both staying at a hostel; I was taking a break. I’d been cycling down the west coast of Australia from Darwin down to Perth. It was tough sometimes, temperatures of 50 degrees. I took nine months to complete this 10,000-mile trip cause I was stopping and staying at Aboriginal camps, cattle stations; I was living a life. So anyway, I came down there, and within this five-minute window that we had to coincide, we met, and we kept in touch. These were the days before email, so via poste restante, really old fashioned. Then she lived down in Australia with me for a while because I was travelling so much; I was away months and months, some of my assignments lasted 14 weeks. So I’d travel around, and she would be back here in St Leonards with her family. So it made obvious sense to be based here. Now with travel restrictions, I’m here all the time.

“I’ve been contributing to National Geographic for 25 years. As travelling has been out of the question since last March, so no travel assignment; I picked up my camera and bike and set a project for myself.”

I’ve always been an early morning person, so I would get up and head out on my bike. So, I was gone for about four weeks on my last international assignment, February to March 2020; it was for The New York Times, a story about the world’s great Panama hat, weavers. So I came back here hours before the lockdown. I passed through Madrid just as they closed everything down and arrived here into lockdown. I couldn’t do much else with my time, so I headed out on my bike with my camera and tripod. I’ve always loved the romantic side of travel, so I thought we have these beautiful lanes in the South East, with a storybook quality to them with a seafront. Perhaps with a mythical holiday, romantic escapism feeling, you know, the old golden age of cycling idea. So I started shooting that. I had this idea, and it grew. To shoot the images that I’m doing requires a whole different photographic skill set. There is so much to learn. I was setting up my camera and riding into the scene; that’s how it started.

You are the photographer and subject, how is that possible?

Roff. Well, I use something called an intervalometer, which looks like a cable release. You push a button, and it’ll fire the shutter, but it is programmable; you can set for anything from one second to 99 hours and determine how many frames you’d like it to fire 1, 2, 5, 10 empty out the whole card, whatever. So I have a tripod, a DSLR pro camera, and I take five lenses with me, three Zeiss and two Canon lenses. I started by riding into the frame; I’d come back and study the results because I had a very definite vision; I mean, I wanted it to be art; I’m influenced mainly through painters, Hopper, Turner, Monet. I want my images to be aesthetically pleasing. I would look at one of my shots and think, well, I needed to be six inches over on the road because my head was not in the right spot; it’s confused with the shadows. And I started learning; it took a lot of studying. I was planning my shots; it isn’t a case of me going out riding and thinking to myself, oh, let’s see what happens. But generally, I’ve got a pretty good idea of where I’m going. I know when the sunrise is to the minute, and the tide time-tables. Sometimes I incorporate the moon where I can so I know the moonrise and moonset.

Extended interview - This part of the interview was not printed in RyeZine 3.

“Sometimes, you can put yourself out. I mean, I wanted to get a very steep hill in shot. I’m coming out of a tunnel of leaves with a backdrop of the Sussex countryside. But the hill is like 15%; I did that ride and shot 35 times one morning with the camera in the same position.”

What is the plan for the project, to keep on documenting the area, a book, an exhibition?

Roff. I’m on the prowl for something. I’ve got quite a large body of work now. I had thought, I’d like to go through the seasons with the shots. I have thought about a book and exhibitions, but I still hadn’t gotten images of a couple of things yet. A few Sundays ago, there was a thick fog, and I went out, over the lanes; the fog was perfect; you get this dark shadows and grey background that frame the cyclist (me). I was out for seven hours and came back utterly nakered.

I studied the landscape a lot and the streetscapes, because you know, the sun isn’t in the same position in the sky. In the summer I’m out. The earliest I’ve left home was 2:45 am.

Almost all of my shots are from a 12-mile radius of home; some are from a 6-mile radius, and I’ve several hundred images to date. This marsh road runs from Cooden to Pevensey; I’ve got well over a hundred photographs just on that road. It’s only a few miles, that if you drive it in the middle of the day, you would think why here, I mean it’s flat, dead, nothingness, but you go there, and the mornings for dawn, the mist and the marsh coming to life, it’s a whole different world.

• We think this project would make an amazing exhibition and book. Here is a selection of six of Roff’s breathtaking images.